B E D O U I N S O F T H E W I N D

O N E H U N D R E D Y E A R S

by Danish Farhan

A poetic memoir chronicling 100 days spent with a Bedouin in the deserts of the Dhaid. Through quiet observation and immersive storytelling, Danish captures the fading rhythms of Bedouin life—marked by silence, tradition, and deep connection to the land.

When strategist and filmmaker Danish Farhan left the city to live for 100 days in the desert, he wasn’t chasing a documentary film. He was chasing something quieter: the last echoes of an ancient rhythm, a culture carried in memory and silence, not monuments. This book was born from untold moments that couldn’t be captured on camera.

S H A R E T H I S

I N S I D E T H E B O O K

Structured in three parts, at once memoir, oral history, and cultural meditation, this book is a bridge between worlds — modern and timeless, spoken and silent, remembered and nearly forgotten.

P A G E S

C A T E G O R Y

207

Memoir, Culture

G E N R E

F O R M A T

Non-fiction

Paperback. Digital

L A N G U. A G E

R E L E A S E

English

Sept 2025

Part I — 100 Years Behind Us

Eleven lyrical essays tracing the unwritten history of Bedouin life through wind, tents, language, and silence. It captures how a people lived in rhythm with the stars and the sand, before the arrival of borders, oil, or time as we know it..

E X C E R P T S

-

I arrived in Dhaid expecting silence. That’s what the city had taught me to anticipate from the desert — an empty stillness, a kind of nothingness wrapped in beige. But what I found was motion. Not in the way cities move, fast and loud, but in a rhythm so ancient and unhurried it felt like breath. The desert didn’t sleep beneath the sand. It moved with it.

-

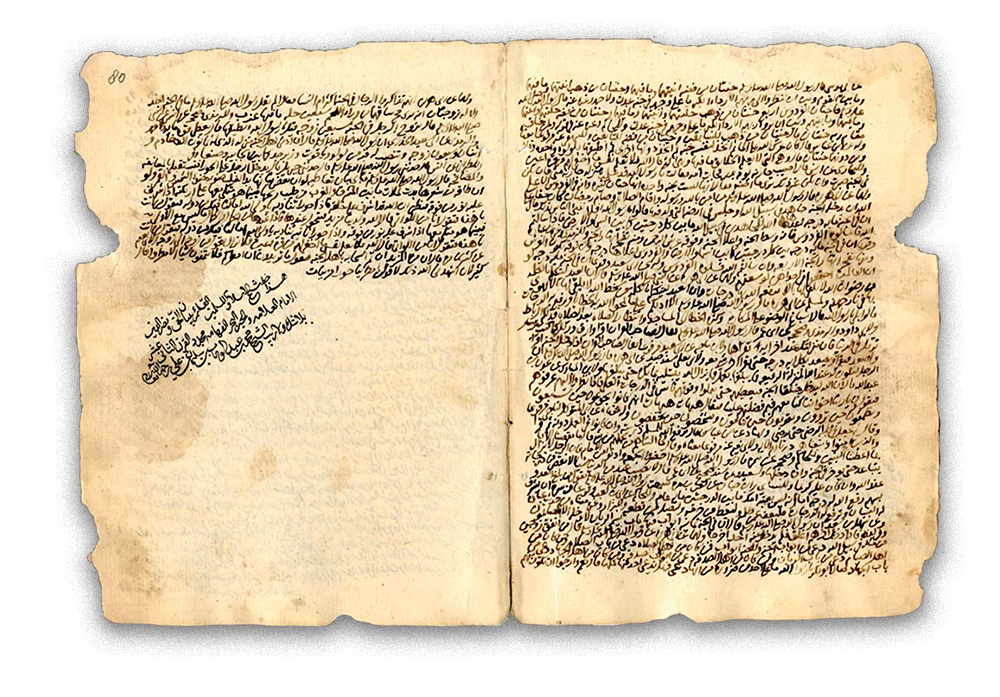

In my time among the Bedouins, I discovered something no classroom had ever taught me: Arabic didn’t come from the Arab world — it created it. The identity we now call Arab wasn’t drawn from borders or bloodlines, but from a shared language that could carry memory across time and silence.

-

The women I saw did not seek visibility. They did not need it. Their influence pulsed through the routine of the day — the way food appeared at exactly the right time, how the children listened more closely when a grandmother cleared her throat, how a glance between sisters could redirect the energy of a room. These were not women waiting to be empowered. They were already holding the fire.

-

Justice in the desert wasn’t written down. It was witnessed. It took place in the open, beneath the stars, beside the fire. No gavels. No robes. Just men gathered on woven mats, each bringing presence and memory. The sheikh would listen more than speak. Resolution came not from argument, but from alignment

-

The lines that divided nations weren’t drawn in the sand — they were drawn in offices, far away. And yet, they changed everything. The tribes who once followed rain now needed permits. Memory was no longer enough — maps took its place.

-

In the early records of empire, Bedouins were translated into categories. Names like Mahra, Duru, Bani Yas — not as stories, but as columns in ledgers. But in the desert, a name wasn’t a label. It was a lineage. A rhythm. It was not written — it was recited.

-

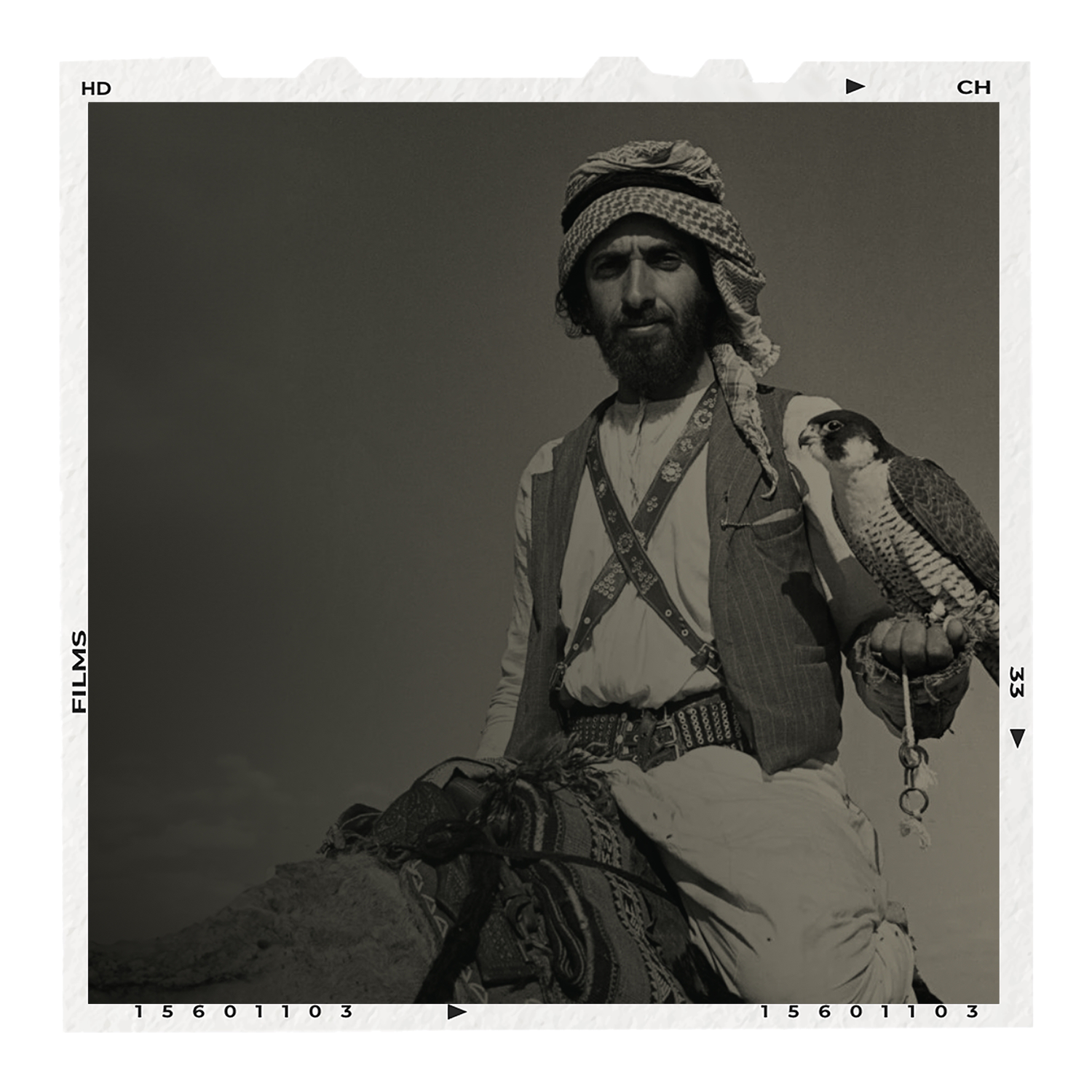

There was a sacred trio that shaped survival: the falcon, the date, and the blade. One hunted, one nourished, one defended. But they were more than tools — they were identity. To master them was to be anchored in a world that gave nothing freely.

-

Progress arrived quickly. One generation lived by camel; the next by Land Cruiser. Cities rose, clocks took hold, and silence grew rare. But deep in Dhaid, the old rhythms haven’t vanished — they’ve adapted, quietly keeping pace beside the new.

-

In the desert, poetry wasn’t art. It was architecture. It held history, memory, grief, satire, love — all passed mouth to mouth, line by line. Nabati wasn’t written, but it survived. Not as performance, but as presence. Truth spoken in rhythm.

-

Camel racing wasn’t a hobby — it was inheritance. From grandfather to father to child, the bond remained. Today, robots replace jockeys and camels carry GPS chips, but the feeling Abdulaziz described remains unchanged: ‘There is nothing like this feeling when your camel wins, and the world knows your name through him.’

Part II — 100 Days with Them

Distills Danish’s desert immersion into 30 field journal entries — moments of stillness, camel walks, evening fires, and unspoken trust. Each day stands as a vignette of presence, revealing the quiet power of observation over explanation.

E X C E R P T

Day 14 — After the Last Sip

6:10 AM, Abdulaziz’s majlis, Dhaid

The fire had softened to coals. The final cups of gahwa sat emptied in the sand. A man wiped the rim with a cloth. Another adjusted his keffiyeh. No one moved to leave. No one spoke.

Where I’m from — In Dubai, I would’ve tapped the table and said “I’ll let you go.”

A quiet question — Why does silence grow heavier after the last sip?

Part III — 100 Lessons I Learnt

One hundred poetic reflections — each formed in the dust and discipline of the desert. These are not lessons in the traditional sense. They are philosophies in miniature — learned not through teaching, but through presence.

The coffee is never full.

Bedouins serve gahwa in small, half-filled cups. Not because they’re stingy, but because refilling is part of the relationship. Every new pour is a new question — are you still with us? Do you want more of this moment?

The one who pours is as important as the cup he offers. You don’t gulp coffee here. You share it, slowly. You let it breathe. Like trust.

L E S S O N # 9

L E S S O N # 84

Time bends around you.

AI stopped checking my phone by the second week. Not by rule, but by rhythm. Time in Dhaid wasn’t hourly. It was sensory. The day began when the first cup was poured. It ended when the last story softened into silence.

No watches. No alarms. Just the sky, the sand, the sound of a familiar gate closing. When time is measured in meaning, it slows.

Before the book, there was the film

B E D O U I N S O F T H E W I N D

F R E Q U E N T L Y A S K E D Q U E S T I O N S

-

Bedouins of the Wind is a poetic, observational documentary that follows Abdulaziz Al Tunaiji, a revered camel breeder and racer from Dhaid, UAE. Through a lens of quiet intimacy and cinematic storytelling, the film captures his life, his camels, and the timeless rhythms of Bedouin tradition amidst a rapidly modernizing world.

-

Danish Farhan is the writer, director, cinematographer and editor of Bedouins of the Wind. A storyteller, strategist, and cultural observer, Danish brings a deeply personal lens to the project, shaped by his upbringing across desert communities in the UAE. His work blends cinematic craft with lived experience, through photography, paintings and writings. This film is both a tribute and a quiet rebellion — a way of preserving memory in motion. More on danishfarhan.com and Instagram.

-

Abdulaziz is not just a central character — he is the heartbeat of the film. A man of few words but deep wisdom, Abdulaziz is a government leader by day, master camel breeder from the Al Tunaiji tribe by night, known for his unmatched bond with his animals and his role as a living link between generations of Bedouin knowledge.

-

Yes. The book was born from the same journey that produced the film Bedouins of the Wind. But where the film captures image and presence, the book goes deeper into reflection — threading together what couldn’t be said on screen.

-

The director Danish Farhan is an expat who grew up around the culture of camel racing and desert life. This unique insider/outsider perspective lends the book an emotional authenticity — both as a tribute and a personal reflection on a fading world.

-

The title is a metaphor for a people shaped by movement, silence, and the natural world. It evokes both the freedom and fragility of Bedouin life — drifting like wind across the sands, carrying memory, legacy, and the quiet endurance of tradition.

-

It’s both. It blends lived experience with cultural record. While deeply personal, the book draws from history, poetry, anthropology, and oral traditions — grounding its reflections in real places, dates, people, and practices.

-

Not at all. The book stands on its own. But watching the film will deepen your understanding of the landscape, the pace, and the faces behind the words.

S H A R E T H I S

A B O U T T H E A U T H O R

Danish is a Dubai-raised, self-taught artist, filmmaker, photographer & cultural observer. A university drop-out but also an honorary doctorate recipient, his work is a study of the in-between: where truth lingers before words claim it. He has spent 40 years in Dubai.